Healthcare is going digital at a rapid pace. A recent article by McKinsey & Company titled ‘How pharma can win in a digital world’ outlines emerging trends in digital health and how pharma needs to evolve to keep up with the times.

A number of predictions in this article are, I believe, misguided and reflect a common, but incorrect understanding of the potential of digital in health.

Prediction # 1: “Patients are becoming more than just passive recipients of therapies”

Patients have certainly become more knowledgeable about their own health and about available therapies. And hopefully, health-related apps are helping people lead a healthier lifestyle and stay on top of their medical conditions and medications. However, patients have never been passive recipients of therapies. Patients have always had the choice of taking or not taking their pill, cutting it in half, skipping a dose, forgetting to take it, taking it with food when they are not supposed to etc.

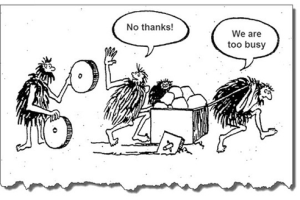

Having served pharmaceutical clients for more than a decade, I have frequently observed that it is difficult for someone within the industry to understand that the medicine they are producing is not the be-all and end-all of a patient’s existence. Life is a busy thing. You work, you look after your family, you eat, you entertain yourself, and you may have a health problem that benefits from taking a medication. The act of taking a pill consumes a fraction of your time and attention. Medicines for health issues that are non-symptomatic may be forgotten because the patient does not feel sick. Medicines for chronic, life-threatening conditions may have suboptimal compliance because the patient would rather not be constantly reminded about his or her precarious situation. For acute conditions, compliance wanes as soon as the patient feels better. Side effects deter patients from taking their pill, etc. Compliance would not be such a huge unsolved problem for pharma if patients were ‘passive recipients of therapies’.

Prediction # 2: “Patients will be actively designing the therapeutic and treatment approaches for themselves with their physicians”

I have read this type of statement numerous times in articles about the future of pharma. Perhaps I am lacking understanding of what’s technologically possible nowadays, but for now let’s assume I have a pretty good handle on it. Designing a pharmaceutical product is an extremely specialized and complex process that involves scientists and labs. A chemical or biological compound with certain properties is created to address a specific health issue, and this compound cannot be easily customized. Rather, it is created and then subjected to rigorous testing, costing hundreds of thousands of dollars (or more), and if it does not hold up to scrutiny, then it’s back to the lab for more experiments and tweaking before another round of expensive testing resumes.

Physicians who spend most of their time in clinical practice do not design therapeutic and treatment approaches. They are merely the retailers of those approaches, acting as consultants to their patients and advising them which approach may be best suited for them. And patients will not be actively designing their own therapies unless they are experimenting with mixing pills and brewing up concoctions of their own invention (caution: don’t try this at home, kids!).

With substantially increased access to information patients can play a much more active role in selecting treatments, but they will not design them.

Prediction # 3: “Medicine will be personalized to address individual patients’ needs” (not in McKinsey article, but can be found in many other publications on digital health).

The move towards personalized medicine is certainly well underway. However, it does not mean that a therapy will be designed on the spot for the individual sitting in front of his or her physician. Again, the physician is the expert mechanic using existing wrenches and bolts to fix the car. The inventor who comes up with new wrenches and bolts does not deal directly with the customer whose car broke down.

Personalized medicines are medicines that target issues more precisely than was previously possible. While physicians used to set off a grenade to blast away your breast cancer, and half of your body as well, they now use a precision rifle that locks in on the malignant area and eliminates not much else. And depending on your genetic profile, there are different bullets that are most effective for your particular type of problem. So the array and precision of weaponry in the physician’s arsenal has increased vastly, and affordable genetic tests have contributed to better targeting of the weapons. But none of these things are designed on the spot, while you’re sitting in the examining room, nor will this be possible for a long, long time.

Explanation: Poor understanding of digital vs. physical contributes to common misperceptions

How do these misconceptions come about and why do smart people write these things?

The past five to ten years of our experience of living in a digital world have greatly impacted our beliefs in how easily things can get done and our feeling of agency. Want to customize your new car? Just click on the features that you want – sunroof, heated seats and the colour red – and you can get this exact model without any effort on your part. Select the perfect outfit? Choose the style, colour and size, and get it delivered to your doorstep the next day. Don’t like part of your video? Just delete and replace.

The ease of these digital experiences has gotten us into the mindset that things can be designed instantaneously, delivered rapidly and modified on the spot. We rarely think about the physical realities that enable our digital experiences. To give you the experience of ‘designing’ the perfect outfit for yourself, the maker has to come up with new styles to attract your desire, run efficient manufacturing to put the piece together with acceptable quality and at an affordable price, ensure the supply chain to enable the manufacturing, build in agility to adapt supply to demand quickly, and create a distribution system to bring the piece to you. All of these things are not done through click of a button, but through the hard work of setting up systems, negotiating agreements, fine-tuning machinery and materials and implementing physical processes.

It’s the same for pharmaceutical products. They are chemical compounds, after all.

Digital opportunities

However, the potential of digital solutions to transform the way we care for ourselves and the way healthcare is provided to us is undisputed. From life tracker apps that help you remember to take your pills on time to smart contact lenses that monitor blood glucose levels without pricking your finger to ingestible sensors that give you peace of mind that your schizophrenic brother has actually taken his medication, digital interfaces, algorithms and sensors can deliver great value to the patient.

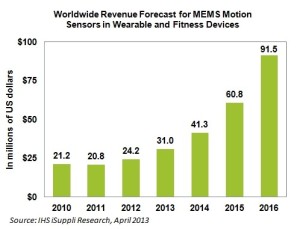

The question is how this translates into business opportunities. Many people believe that pharmaceutical companies should transform themselves from being “a products-and-pills company to a solutions company” (see McKinsey & Company article). The idea is to not only provide medicine to the patient but also digital tools for monitoring of the patient’s condition, for communicating with the patient’s circle of care, for scheduling and reminders, for supporting rehabilitation after events and for outcomes tracking. From a patient perspective, this could certainly be a valuable offering. From a business perspective, the value proposition is less clear.

First of all, pharma companies do not typically have the expertise to develop digital solutions in house. Some form alliances with tech companies. Novartis and Google are developing smart contact lenses for people with diabetes and are scheduled to start trials this year. Otsuka and Proteus Digital Health have teamed up to embed a digital sensor into a schizophrenia medication to track compliance, and have submitted the first digitally enhanced new drug application to the FDA. J&J has set up a series of incubators and rewards startups for coming up with interesting ideas in digital health. Merck sponsors health hackathons.

What does the pharmaceutical company get out of this? Will physicians choose their medication over competitive products because it comes with a digital value add? Is the digital component just another cost factor that is necessary to stay competitive these days, or is there a revenue model somewhere? It seems that there is currently a climate of experimentation without a clear business model path ahead, not unlike many other areas of digital development.

In crowded markets with little product differentiation, it is possible that the companion app could become the deciding factor in recommending one drug over the other. However, it is hard to imagine that it would play any role if there were differences in efficacy or side effect profile between the compounds. A tricky little question is also what to do with patients who need to switch off one product and go to another. Should they be denied continued usage of the app?

To be truly solutions providers, pharma companies would need to be structured differently, around disease states, not around products. It would make more sense to form a company that is, say, a ‘cardiology broker’, offered great digital tools to manage a variety of cardiologic conditions and give patients access to the full gamut of cardiology drugs available. The sales reps for this company would not overtly or covertly ‘push’ one or two drugs, but they would advise physicians on what is new in the field and impartially discuss the merits of the different options. There are some attempts of pharma companies to become leaders in a therapeutic space and assume the role of expert provider – for example Roche or Novartis in oncology, where both companies have a large product portfolio. However, by and large, this type of business model does not apply to how pharma companies are organized and how they make money currently. It would be more applicable to private payors, and we see some organizations in the U.S. moving in this direction.

Low-hanging but sour fruit

The obvious area where digital tools can be used very effectively to drive engagement is patient-related. Arguably, a more engaged patient will likely be more compliant and stay on therapy longer, resulting in immediate benefit to the bottom line.

However, while many companies try to be patient-centric, any direct engagement with a patient carries the risk of an adverse event report with it. While adverse event reporting systems have been set up to keep patients from harm, unfortunately, reporting requirements are ridiculously broad. Nobody is keen on generating massive amounts of adverse event reports for their drugs. So digital engagement of patients has to be done with all sorts of caveats to reduce the risk of learning about an adverse event. Some companies stay away from direct engagement with patients altogether for that reason; others have taken the plunge and struggle to come up with creative ways around the problem.

Another challenge in engaging with patients through digital tools and platforms is finding appropriate engagement formats for particular audiences. A platform that has been designed to help kids with pain through gamified challenges and ‘levels’ may not be the right approach to engage a 70-year old cancer patient. Very little testing and research has been done to date to find out what tools best support patients with certain conditions. The key here is to be open to a multi-platform approach. While a game may be great at motivating one audience, a combination of text reminders and phone support may be best suited to keep another audience adherent to their treatment. Unfortunately, many of the vendors that design patient engagement tools on behalf of pharma are either all digital or not digital at all. What would be needed is a new type of vendor who can pull together various types of tools and customize them for a particular target patient population.

Low-hanging sweet, sweet fruit

One area where pharma could employ digital innovation easily and with sustained impact is in the way companies communicate with physicians. While almost everyone has switched to iPads for detailing over the past few years, pharma companies (in Canada, my home turf) still have limited understanding of how digital can be used to improve access and deliver value to physicians. Knowledge about different forms of digital engagement is lacking in marketing departments where people think Twitter and Instagram are for self-absorbed teenagers with too much time on their hands. Also, there is a feeling that digital is not important to the physicians who are core to the business. However, as one year after another go by and younger physicians become key opinion leaders and high prescribers, companies may find that they have missed the boat in establishing a digital rapport with these individuals.

Only recently have some companies started to think about conducting media audits and finding out from their core target how they use digital tools and what might be of value to them. Putting some effort and resources into understanding the myriad of different ways digital can be used, and physician preferences in this regard is relatively simple and will almost certainly have a payoff within a five-year timeframe. There will likely be some resistance from the sales folks who tend to see alternatives to face-to-face engagements as a threat to their position. However, I believe that the 21st century sales rep needs to be an expert in offline and online relationship building. Pharmaceutical companies need to figure out how to integrate different forms of digital and non-digital engagement optimally, and create internal structures and tools to maximize value for the customer.

McKinsey & Company article source:

http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/pharmaceuticals_and_medical_products/how_pharma_can_win_in_a_digital_world

Image sources:

‘Digital health collage’: Made the image myself

‘The alchemist’: https://openclipart.org/detail/222415/alchemist

‘Tools’: DeWalt DEWALT DWMT72163 118PC MECHANICS TOOL SET on http://toolguyd.com/dewalt-ratchets-sockets-mechanics-tool-sets/

‘Cartoon’: I’ve seen this cartoon on the web many times, but don’t know who made it originally. I’ve copied it from https://effectivesoftwaredesign.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/wheel.png?w=640